Posted by Carol Drinkwater

http://the-history-girls.blogspot.com/2025/06/born-out-of-wedlock-by-carol-drinkwater.html

I am a week away from publication of my latest novel, ONE SUMMER IN PROVENCE. 3rd July 2025. It is always an exciting as well as a nerve-racking time. A broad synopsis of what the novel is about: a British couple, Celia and Dominic, are living on a vineyard in the south of France. A vineyard that was inherited by Celia when her father died a decade earlier. Celia has decided to throw a huge summer party to celebrate the growing success she and her husband are making of their wine production. A few days before the big August bank holiday weekend when the party will be in full swing, Celia receives a forwarded letter from a man, David Hawksmith, who claims to be her son; the son she gave up at birth in 1977. David's existence is the outcome of a traumatic incident from Celia's past that she has never spoken about, not even to Dominic. Celia invites David to the party. Dominic graciously welcomes him (and David's unexpected and rather curious travelling companion) even though he has his doubts about the veracity of David's claims.

The book has elements of mystery but, ultimately, it is a story of Betrayal and Belonging set against a backdrop of all the glorious ingredients - food, sunshine, scents etc - of living along the Mediterranean coast in the south of France.

The Irish Times, in a recent Q and A, asked me whether the fact that I don't have children of my own had been the seed, the inspiration, for the novel. Giving up a child born out of wedlock is a very big issue in Ireland. Only two weeks ago, a dig began in search of the bodies of babies whose mothers were obliged to give up their "illegitimate" offspring during the last century.

https://news.sky.com/story/opening-the-pit-dig-for-remains-of-800-infants-at-former-mother-and-baby-home-in-ireland-begins-13384111?fbclid=IwY2xjawK8yglleHRuA2FlbQIxMQBicmlkETB5RzI4SXF3eFBab042VmNyAR7960m6fL8n0J55ru2FjHnpkPSRQPp9TKphdWrgRFnD2zV0qQ8HeqYtXUjj6A_aem__xN9uAsQA5bsM7CkprKizA

I have written a little about this subject before in one of my earlier History Girls blogs. Via the link below you will read that Ireland's right to abortion was not made legal until 2018.

http://the-history-girls.blogspot.com/search?q=carol+Drinkwater+Irish+childhood

Abortion was made legal in Britain on 27th October 1967, and came into effect on 27th April 1968. In theory, this means that Celia, the leading character in ONE SUMMER IN PROVENCE, could have legitimately terminated her pregnancy, but, for reasons revealed in the novel, she did not.

The choices for young pregnant women before the late sixties in Britain were: a termination of the pregnancy (frequently a risky abortion, a backstreet illegal business), a hasty marriage, for some a shotgun wedding, or give up the child at birth for adoption.

In my novel, the young Celia gives birth to her son and, four days later, the child is taken from her for adoption. All she knows about the boy is the Christian name she has chosen for him, David.

Ghosts from the past.

I am fascinated by secrets that step out of the shadows of our own lives and others' lives. The lives of those close to us. My mother was expecting me when she married my father in October 1947. I often joke about the fact that I was with them on their honeymoon in Devon. However, this was a fact I only discovered, by accident, when I was about ten or eleven. I found a stash of their honeymoon pics and calculated the dates! The subject had never been spoken about and when I confronted my parents with the question, they (both Catholics) were a little sheepish, but did not deny the fact. Why should they? I have, since that discovery, perceived my conception as one fired by love and passion. Would they have married if Mummy had not been pregnant with me? I believe they would, but who can say? The choice they made was to keep the baby, marry and start a family.

I love to be by the sea - I live overlooking the Mediterranean. I crave its rhythms and I have asked myself whether this has anything to do with the fact that my parents were happy on their honeymoon. A happiness that was tested in a relationship that was tumultuous even though they stayed together all their lives and my mother was deeply committed to her marriage. She loved my father loyally till the day he died, forty-six years later. Her face and her demeanour at his deathbed I will never forget.

Now that both my parents are gone, I deeply regret all the questions I never asked. How did Mummy feel the moment she discovered she was pregnant; was she frightened, elated, guilty? What were the circumstances when she discussed her situation with Daddy? What was his response: "Let's get married, Phil" ... Was his willingness to tie the knot instantaneous? I know that they had been expecting a boy and had decided to Christian me Charles!

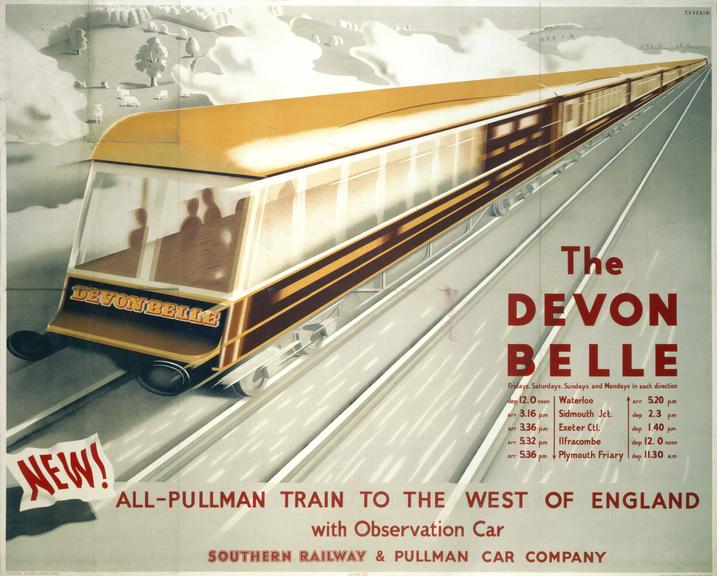

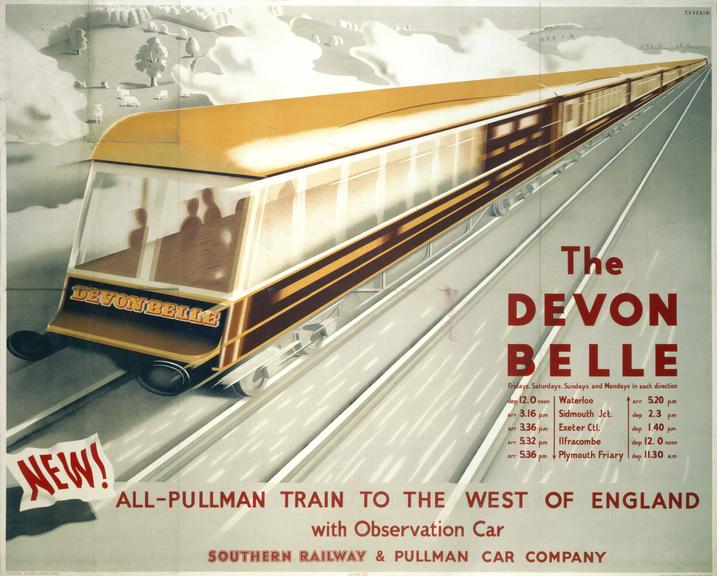

The morning the newly-weds, my parents, were boarding the luxurious Devon Belle train at Waterloo station heading to Ilfracombe in north Devon for their honeymoon, my father discovered that he had won the Football Pools. His win was the staggering sum of almost one hundred pounds. It was a fair fortune in those years of austerity after WWII. Mummy told me some years later that it felt as though their marriage had been blessed. It was all their wedding presents rolled into one. As an Irish country girl who had relocated to London during WWII to train as a nurse, she was far from home and her family. The wedding was a very quiet affair with only my father's brother and my mother's younger sister in attendance, as far as I am aware.

The Devon Belle was a luxury passenger train which only began service in June 1947 so my parents would have been early travellers. I wonder, before his pools win, how my father, so soon home from life in the RAF entertaining the wartime troops in Africa, could have afforded to splash out on such a treat. But it does seem to suggest that he was celebrating their union, that he wanted to give my mother, pregnant with their first child, the best that was on offer. A luxurious and memorable debut to the life ahead of them together in post-war London.

Last week I was in London recording ONE SUMMER IN PROVENCE for audio. Reading the novel as an actress is quite another eye to when I am working on the text as a writer. This time, as I read, a period from my own teenage years came flooding back to me. Bromley in Kent, in England in the early 60s, a little earlier than my principal character, Celia's teenage years in a small provincial town outside Bristol. Without realising it, subconsciously, I must have taken from my own experiences of this era and interwoven it into Celia's story in the novel.

When I was a late teenage girl, the battle to legalise abortion was underway. David Steel, Liberal MP, later leader of the Liberal Party, was responsible for introducing as a Private member's bill, the Abortion Act 1967. Fortunately, I had no need of the liberating results of this act once passed. Even so, as a teenage girl growing up, educated at a rather strict Irish convent, the waves of such a progressive bill would have been in the news and in debates all around me. As well, I must have had some awareness of the trials and terrors for young unmarried women who found themselves "in trouble" in the days before abortion was an available choice for them.

The episode that came flooding back to me as I was recording my novel last week was of a completely forgotten incident. It was the case of R., a girl in my class at the convent. We both would have been about fifteen at the time. R. discovered that she was pregnant. In our middle-class, Catholic-educated circles, this was completely unheard of and very shocking. How did R. deal with her situation? She said nothing, packed a bag and just disappeared. It was a scandal. Her parents, of course, were fraught with worry. I have a clear image of her mother and father paying a visit to our house one evening after school. We were all gathered in the sitting room, which in itself was rare. The white and gold-flecked three-piece suite was usually covered in dust sheets to keep it clean and protected from the light. The room was rarely used. Mummy kept it immaculate for "special occasions". Well, this must have been deemed a special occasion. I sat in a corner. Our guests remained standing. R.'s exceedingly tall mother was chain-smoking. (Smoking in Mummy's pristine sitting room!) She was clutching a small ashtray shaped like a shell in the palm of one hand. The reason for the gathering was information. "We need to hear what Carol knows about R. Her movements, her companions, before she fled."

Or had she been kidnapped, abducted, murdered? Were any of these scenarios ever considered? I don't remember. Certainly the police had been called in and a search for R. had been set in motion. It wasn't known at this stage that R. had gone of her own volition nor that she was pregnant. I had no information to share with the grieving adults towering over me. R. had not confided in me - we weren't that close - and I had not overheard any chatter in the classrooms. I could shed no light on the crisis. R's mother was in tears as they exited our house. I felt so bad about their situation that I was almost inclined to run after them, invent a tale, but I knew better than to create false leads.

It was at least another three weeks before R. was eventually tracked down, It was then her parents discovered that their daughter was pregnant. This was two or three years before David Steel's Abortion bill. R. was sent away somewhere unknown to me to give birth to the child who was then immediately handed over for adoption. My classmate never returned to the convent. She became a girl from our childhood whose story was not spoken aloud. Her parents split up, as I remember. Tragedy had befallen the family.

R. was a young woman shamed. From there on she and the "unsavoury business" was only spoken of in whispers.

What happened to R.'s child, her son? Did she and he ever make contact, did they find one another at some point later in their lives? I have no idea. I sincerely hope that there was some kind of happy ending to the tale.

In ONE SUMMER IN PROVENCE, Celia's son, David, contacts her out of the blue. A forty-seven-year-old man claiming to be the son she gave up at birth comes knocking, or rather, sends a letter requesting a meeting ... How does a mother respond? Invite the stranger into your life, welcome him as long lost kin ... Or deny his existence? Refuse to see him?

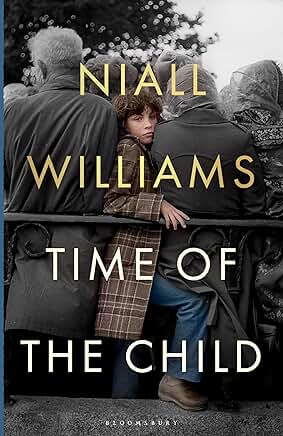

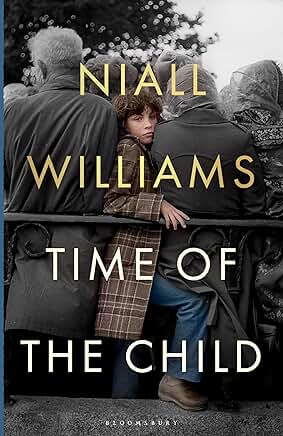

Earlier this year, I was honoured to be one of the two judges for the very prestigious Listowel Literary Festival's 'Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year Award.' Settling on our overall winner was very tough; the standard of fiction being published by Irish writers right now is mesmerisingly good. The prize went to Niall William's, Time of the Child. Williams' story is set during the season of Advent in the year of 1962 in a small (fictional) village over on the west coast of Ireland. An abandoned baby is found in the churchyard and taken in by the local doctor and his unmarried youngest daughter ... The prose is luminous and the story, compassionate and heart-wrenching.

Coincidentally, having read fifty novels for the Kerry Prize, I am now reading another Irish novel, also delicately crafted. The Boy From the Sea from debut novelist, Garrett Carr. It is 1973. A baby is found in a barrel off the shore of a small coastal Atlantic town in Ireland. A local family adopts the boy ... Beautifully written, full of wry humour.

Every conception offers up the possibility of an untold story; a world of choices, of future bondings or terminations. Of aspirations and dreams dashed or built, of love washed up on unexpected shores.

I beg to be forgiven for placing my novel on the same page as the very fine works of Williams and Carr. These are three very different stories. What they have in common is that each centres on the ripples and (tidal) waves caused by the arrival of a boy born out of wedlock. Interestingly, the other two are both written by male authors.

I hope you will enjoy ONE SUMMER IN PROVENCE. It is receiving some splendid feed back. It is a LoveReading Book of the Month for July. Available at all good bookstores and on Amazon etc. If you are outside the UK, Blackwells will have it in stock and they ship worldwide for free. Here is the link:

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/One-Summer-in-Provence-by-Carol-Drinkwater/9781805462767

Have a wonderful summer. If you happen to be in Britain, Ireland or France during July, here, above, are a few of the events I will be talking at. It would be lovely to see you at one or other of them.

Enjoy your summer reading.

www.caroldrinkwater.com

http://the-history-girls.blogspot.com/2025/06/born-out-of-wedlock-by-carol-drinkwater.html